by Marc Masurovsky

In order to ensure trouble-free border crossings, it helped to be on familiar terms with the police, the military and the border force which required the recruitment of reliable locals to help ferry these people and their looted property into Spain. Added to that mix the complicity of security services, government officials, businessmen, “notaires” and lawyers to shield you from trouble and officialize future commercial and financial transactions. The local populace staffed the smuggling chains. To the extent possible, local and provincial officials ensured the smooth functioning of these semi-clandestine operations for a fee. In this regard, local Falangists and members of the Guardia Civil were of assistance.

The main open crossing point for Nazi war criminals, Fascists and economic collaborators (with a little help from French and Spanish police and military) lay between Hendaye, Pyrénées-Atlantiques (France) and Irun, the Basque Country (Spain), and from there to San Sebastian—about 20 km south of the border. That ended in August 1944 when the Allies pressured Spain to put an end to the northward traffic in wolfram, a strategic ore used by the Nazis in the production of steel alloys for their war effort. The closure of the official Franco-Spanish border placed the clandestine routes across the Pyrenees in the spotlight.

These routes ran across the western Pyrenees (Pyrénées-Atlantiques), linking French hamlets and small villages to localities in Navarre and the Basque country, within a 50 km radius. Based on Allied intelligence sources, these clandestine cross-border routes were used most often:

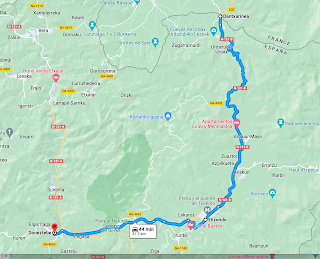

1/ Dantxarinea, France (or Duncharinen)—Elizondo, Navarre, Spain—Doneztebe-Santesteban (Spain)

This route ran an estimated 40 km by road.

Two men, Andres [Andreas] Lazaro, from Elizondo, and Elso, from France, managed a “chain” for ferrying goods from France to Spain for the account of German interests. It is worth noting that Elizondo was also used as a local turnstile for smuggling gold acquired in the Western Hemisphere and ferried across the border to France as well as Nazi looted gold coming into Spain.

2/ Bidarray [Pyrénées-Atlantiques] (France)—Errazu [Erratzu] [Navarre] (Spain)

After safe passage from Bidarray to Erratzu, Spanish police picked up clandestine border crossers, took them to Elizondo and from there to Santesteban.

3/ Otxondo/Espelette (between the Basque Country and France; on the French side)—Elizondo (Spain)

For unknown reasons, this route was cited by Allied intelligence as a favorite of smugglers.

4/ Anduitzem Borda farm (Sare, France) –Bera (Vera del Bidasoa, Spain)

This line started at the Anduitzem Borda farm in Sare, France. and extended to its end point, the village of Vera del Bidasoa, Spain. It was organized for the Germans by a member of the Guardia Civil named Marquez who lived in Bera (Vera del Bidasoa). It is likely, although not confirmed at this point, that those who were ferried to Bera were taken to Donetztebe/Santesteban.

5/ Eraso-Alcasena line

The Eraso-Alcasena line was used to smuggle gold obtained in the Western Hemisphere at reduced rates and sent illegally to France where higher prices could be obtained. It ran through Elizondo since Señores Miguel Eraso and Alcasena hailed from Elizondo and participated in the smuggling of Nazis and others into Spain through their home town.

Wolfram, a critical ore to manufacture steel allows, was also smuggled through Elizondo into France for German account. Eraso was the main point of contact here. In 1945-6, gold acquired in Western Hemisphere ports with US currency and brought back by sailors to the Iberian Peninsula was sold in Bilbao and from there conveyed via Barcelona and Irun into France where rates are allegedly higher making this illegal gold trade highly profitable.

Miguel Eraso was involved in some manner with this activity and enjoyed close ties to Spanish military authorities along the border. The vicar of Erratzu/Errazu, Padre Apesteguia, was allegedly involved, as well as a cattle dealer named Acien, based in St-Etienne de Baigorri.

Here are some tentative findings:

Elizondo served as a nerve center for much of the smuggling activity in the Navarre region. The main originating points for the smuggling activity were situated within a 35 km radius from Elizondo. Sare (France) is 31.7 km from Santesteban, assuming it was a destination point for activity generated at Sare. In more general terms, Santesteban/Donetztebe acted as some kind of temporary transit station before people/goods spread out to other parts of Spain—Bilbao, Barcelona, Madrid, etc.

Elizondo appeared to be a transit point for Nazis and other “obnoxious” individuals crossing from France into Spain. These people were greeted by Spanish soldiers who then took them to Elizondo and from there 14 km west to Doneztebe-Santesteban.

More to follow…

Sources:

Records of the Office of Strategic Services (RG 226)

RG 226 M1934 Reel 17 NARA

RG 226 Entry 108b Box 220 NARA