|

| Helly Nahmad Gallery, NY |

|

| "Zwei Griechinnen", 1941 |

|

| Sotheby's 1990 |

By Marc Masurovsky

When it comes to confiscated Jewish cultural assets, we are certainly not responsible for errors committed by Nazi agents at the time that they inventoried their confiscations. Those German bureaucrats, many of whom hailed from German cultural institutions, were known for their efficient plundering of Jewish assets which they dutifully catalogued, inventoried, sorted, packed, unpacked, repacked, and shipped to other repositories only to be unpacked again, catalogued, inventoried, etc… When the Allies discovered many of these looted objects, they transferred them to their own repositories where they unpacked these recovered objects, catalogued, inventoried, carded and repacked them, before repatriating them to the countries from which they were stolen in the first place. The years-long cycle of plunder, recovery, repatriation. Rinse, repeat, rinse, repeat.

|

| Record of seizure at Arnold's home, 1941 |

In the case of a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, referred to as “Two Greek Muses” (“Zwei Griechinnen”), painted either in 1926 or 1927, as part of a series of similar vertical works, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) removed “The Two Muses” from a Parisian residence and transferred the painting to the Jeu de Paume in central Paris in early March 1941. At that point, two confiscated Jewish collections entered the Jeu de Paume—Hans Arnhold’s largely Old Master collection on 7 March 1941 and the modernist collection of Michel Georges-Michel which arrived on 10 March 1941. And that’s where our little problem begins: at the registration process.

The staff responsible for processing confiscated objects were ill-equipped to process thousands of objects diligently. A mountain of looted works had to be described, measured, assigned labels, and in some cases photographed, before being stored while deciding their ultimate fate—go to Germany or Austria, or be handed over to local dealers, or…. The ERR bureaucrats in charge of sorting confiscated works and objects upon arrival labeled the “Two Muses” as “ARN 2” and belonging to Hans Arnhold. The painting actually belonged to Michel Georges-Michel (M.G.M.). This imbroglio continued through to the end of the war and…until 2015.

|

| ARN 2, as recorded at Jeu de Paume, March 1941 |

Consistent with Nazi cultural policy, the Two Muses (now titled “Zwei Griechinnen”) were marginalized as a “degenerate” work. Like many similar works—by Dali, Ernst, Masson, Picasso, Braque, Chagall, and countless others—which the ERR did not know what to do with, it was segregated in a remote part of the Jeu de Paume, then crated in early July 1944 and loaded onto the last train commandeered by the ERR from Paris on 1 August 1944 and whose final destination was a Moravian castle at Nikolsburg (present-day Mikulov). Had the train reached Nikolsburg, the Two Muses would have likely been incinerated during a week-long confrontation between last-ditch German defenders and the Soviet Red Army and Air Force in late April 1945.

|

| Rose Valland's inventory of recovered works, 1944 |

The Nikolsburg train broke down outside of Aulnay-sous-bois east of Paris (and was later immortalized in an entertaining film with Burt Lancaster called “The Train.”) The “Two Muses” and hundreds of other modern works were spared from oblivion and returned to Paris where they should have been restituted to their respective owners. “Two Muses” was restituted to Michel Georges-Michel in 19467. However, solely based on the ERR catalogue, it would be difficult for a researcher today to know that it had actually belonged to Georges-Michel and so it was recorded as an unrestituted Arnhold painting. The work never appeared in Hans Arnhold’s restitution records which signaled a definite problem with the records. Furthermore, the Chirico painting stood out like a sore thumb in Arnhold’s conservative collection of fine Old Master paintings. A dissonant esthetic anachronism.

The pieces finally come together

In late fall 2015, the Helly Nahmad Gallery on Madison Avenue, NY, staged an exhibit with Phoenix Art Galleries that highlighted the Muse of Memory, Mnemosyne, partly through Giorgio de Chirico’s works on muses, juxtaposed with Greek antiquities supplied by Phoenix. A New York-based art historian spotted de Chirico’s Two Muses at the Nahmad Gallery and rang the alarm bells. It definitely looked and felt like the one documented as ARN 2.

In early 2016, a separate on-site visit confirmed the match with the confiscated work. Upon inquiring about the provenance of the work, a gallery employee came out empty-handed. At that point, it still was not clear whether the painting had been restituted since it had been erroneously assigned to Hans Arnhold by the Nazi plunderers. Still thinking that the painting had not been restituted, a frantic month ensued with specialists in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the US, scouring archives and art historical sources only to confirm what the gallery had refused to share: the painting had belonged to Michel Georges-Michel, an interwar art critic and artist in his own right. And, most importantly, it had been restituted. Thanks to the cooperation of French cultural officials, German art historians, and restitution specialists on both sides of the Atlantic, a silly imbroglio produced by sloppy and overworked plunderers had not degenerated into a full-blown a transatlantic feud between the heirs of two Jewish victims of Nazi plunder.

Lessons?

1/ Thieves make mistakes. Be prepared to correct them when you realize, based on fresh evidence, that your data are wrong. It’s not you, it’s them. But it’s your duty to fix these mistakes and to inform your public of what you did in an explanatory note, to the extent that you can.

2/ international collegiality and collaboration prevent unnecessary bad blood and complex legal entanglements while promoting higher ethical standards and due diligence in the global art market and among scholars and museum personnel. The search for historical truth is paramount in establishing the bona fides of cultural objects and ascertaining their legal status.

Here is a partial provenance history of “Two Muses” by Giorgio de Chirico, signed and dated 1926, 130 x 70,5 cm. Oil on canvas.

Provenance

Galerie Léonce Rosenberg, acquired from the artist;

Michel Georges-Michel Collection, acquired from Galerie Léonce Rosenberg, Paris.

Confiscated by ERR agents, Paris, in early March 1941;

Transfer to Jeu de Paume, 10 March 1941 where it is recorded as ARN 2.

Set aside by ERR staff to be sold or exchanged in 1942.

Packed in crate “Modernes 34” on 6 July 1944 at Jeu de Paume (BARCH B323/303/27, Koblenz, Germany)

Transferred to Nikolsburg as ARN 2, 1 August 1944.

Recovered by French forces at Aulnay-sous-Bois in late August 1944 and catalogued by Rose Valland as ‘Arnold. Chirico. Deux statues antiques, 133 x70 cm.”

Restituted as “Les deux muses” to Michel Georges-Michel in 1947.

Present whereabouts unknown.

Sales

Rameau auction, Versailles, 15 March 1970

Sotheby’s Monaco, 25 June 1984, Lot 3409, sold as “Les muses du foyer”.

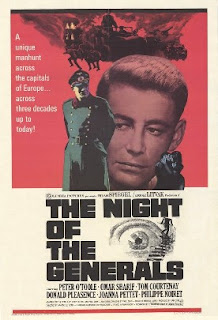

New York, Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Part I, Sotheby’s, 17 May 1990, Lot 60, not sold.

Exhibitions

London, Arthur Tooth & Sons. First exhibition in England of works by Giorgio di Chirico as “Les Muses du foyer” (1926), no. 4, 1928

Maybe exhibit at Galerie Flechtheim, Düsseldorf/Berlin,1930, as Zwei Frauen

Helly Nahmad Gallery, 970 Madison Avenue, NY, late 2015-January 2016.

Select sources:

Database of Art Objects at the Jeu de Paume, www.errproject.org

Bundesarchiv, Koblenz

Archives du Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (AMAE), La Courneuve, France