|

| Rose Valland, c/o Ministère de la Culture |

On 10 November 1949, Rose Valland, France’s point person on repatriation and restitution issues, wrote to Stefan Munsing, then Chief of the CCCP, to inform him on the activities of a recently naturalized American citizen of Jewish extraction living in Paris. His name was Heinz Berggruen. “He flaunts his privileged access to American museums. However, the US Embassy in Paris does not like him. Our suspicions about him grew when we compared his project with the one promoted by Auerbach and Wildenstein.” According to Valland, Berggruen was organizing a sale of paintings in Bavaria in which Georges Wildenstein held an interest. The works being sold had been consigned by Berlin dealers who knew that American clients would be congregating in Munich for that purpose. One of the dealers, a Mr. Buren, apparently consigned two French paintings, one by Corneille de Lyon and the other by Nattier. Valland notified Munsing that France reserved the right to assert its jurisdiction over those paintings and any others offered on the art market. She asked him to take the necessary measures to warn American museums not to deal with these “gangsters” whose behavior is unacceptable.

Munsing’s investigations into Berggruen produced meager results. Berggruen was mostly dealing in rare books on his frequent visits to Bavaria. He also flaunted his contacts in high French circles as well as his familiarity with French customs who “never opened my bags.”

|

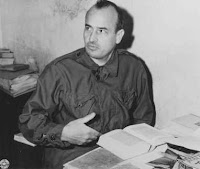

| Theodore Heinrich |

On 13 February 1951, Theodore Heinrich wrote to one of his former MFAA colleagues, Lane Faison. He warned him about his concerns regarding notables (Jewish and non-Jewish) of the art market who might be involved in postwar shady transactions. He was once the director of the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point in the US zone of occupation in Germany, while serving with the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives (MFAA) administration. The MFAA had established the Munich Central Collecting Point (MCCP) in central Munich in May 1945 in order to process and dispose of cultural assets stolen from Nazi victims across Europe. In application of international law, their mission was to identify the place where these assets had been stolen and return them to those countries from which they would then be restituted to the rightful owners. At least in theory… Heinrich suspected that something ominous was brewing in the postwar art market with respect to the fate of “undistributed holdings at MCCP.”

The cast of characters included:

|

| Karl Haberstock |

- Karl Haberstock, Nazi art historian and art dealer who carried out the plans of Nazi dignitaries to acquire thousands of works of art for Hitler’s Linzmuseum project and, in so doing, partook in the spoliation of Jewish collections across Western and Central Europe.

|

| Georges Wildenstein |

- Heinz Berggruen, a German Jewish refugee who settled in San Francisco in the 1930s, returned to Europe with the US Army and established what became one of the most famous art businesses of the postwar era, starting in liberated Paris.

|

| Heinz Berggruen |

- Dr. Philip Auerbach, a Bavarian official who worked closely with Jewish organizations on the question of unclaimed Jewish cultural assets located in the US zone of Occupation of Germany where he worked.

- Grace Morley, a native of Berkeley (CA) and a UNESCO official who headed its Museums division (innocent bystander)

|

| Grace Morley |

It is unclear when and how Theodore Heinrich discovered the “sub-rosa” relationship between Karl Haberstock and Georges Wildenstein. He nevertheless accused Berggruen (Paris), of acting as a go-between between Wildenstein (New York), and Haberstock (Bavaria).

Lane Faison (director of the Munich CCP) was aware of the fact that « many dealers had come to Munich in fall and winter (1950-1) to meet with Auerbach and other officials about Goering’s assets. These dealers believed that some of the Goering treasure would be made available to the art market. Faison condemned this behavior saying that it was antithetical to the spirit of restitution. He made it known that the US would never tolerate such a strategy.

to be continued...