|

| Portrait of Paulus Pontius, Anthony van Dyck |

by Marc MasurovskyAdolphe Schloss spent the last thirty years of his life painstakingly assembling a collection of Old Master paintings—Dutch, Flemish, German, Italian, Spanish and French. When he died on New Year’s Eve of 1910-1911, Adolphe Schloss had collected more than 330 paintings. His widow and children took care of the collection until it was time to send it to safety at the approach of war in August 1939. Four years later, a commando of French and German agents stormed the site where the paintings were hidden at the Château de Chambon in Laguenne, Corrèze. They seized all the paintings and brought them to Paris for “processing.”

After they reached their destination on 10 August 1943, representatives of the Vichy government, senior officials from the Louvre, and German officials proceeded with the dismemberment of the confiscated collection. The Louvre snatched 49 paintings for its permanent collection while 262 paintings were sold manu militari to Hitler’s Linz Museum project, and 22 paintings served as a “finder’s fee” for the person who denounced the collection’s whereabouts, Jean-François Lefranc. The 262 paintings were shipped to Munich for storage at the Führerbau from which they were stolen between 29 April and 2 May 1945, under the very noses of American troops. One of those paintings was the Portrait of a gentleman-Paulus Pontius by Anthony van Dyck.

Before Adolphe Schloss acquired the work by 1896, Paulus Pontius had changed hands numerous times and travelled throughout Western Europe and the United Kingdom. Its earliest recorded owner was Cardinal Silvio Valenti Gonzaga (1690-1756), who held the painting until his death in 1756. Then it conveyed to Cardinal Luigi Valenti Gonzaga (1725-1808), Rome, until 1763 when an art dealer, Hendrick de Leth (1703-1766) acquired it. From there, the painting crossed the Channel and ended up at Peper Harow in Surrey, England with the Midleton Family (we think). It remained in Surrey until 1851 after which time it migrated to London into the hands of Wynn Ellis (1790-1875). By 1896, London-based P. & D. Colnaghi sold Paulus Pontius to Charles Sedelmeyer in Paris (cat. 1896, no. 11, ill.). Sedelmeyer was one of Adolphe Schloss’ main art advisors. Naturally, Schloss snapped up the van Dyck portrait that same year and it remained with him and the Schloss family until its confiscation in 1943.

Munich 1945

|

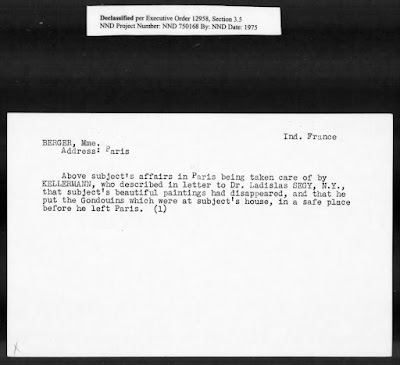

| MCCP card #46622 |

The massive unprecedented and largely unsolved art theft at the Führerbau (29 April-2 May 1945) netted over 1100 paintings. While American troops were completing the liberation of Munich and ridding the embattled city of its most fanatical armed Nazi resisters, Munich citizens were busily robbing Hitler’s administrative office building in search of food, alcohol, and anything fungible with which to survive in war-torn Munich.

Like most of the plundered paintings removed from the Führerbau,

Paulus Pontius went quickly underground. It took three years for Americans to catch wind of its possible location. Until then, its whereabouts had remained unknown to American and French investigators connected with the Munich Central Collecting Point (MCCP), a central processing station for all objects recovered by Allied troops in Bavaria and processed for repatriation to their countries of origin.

Wolfgang von DallwitzThe efforts to locate the missing painting took an unusual turn in February 1948 when Wolfgang von Dallwitz, of Biedersteinstrasse 21 (Munich) told Edgar Breitenbach that he had seen the painting in mid-November 1947 at “the apartment of a friend in Munich” together with two other paintings from the Schloss collection (

a painting by Ludolf Backhuyzen /Schloss 3,

a painting by Abraham van Beijeren /Schloss 8). A Dr. Irwin Sieger had allegedly shipped them from a railroad depot in Göttingen. [Breitenbach to Leonard, “Information concerning stolen Schloss paintings,” 25 February 1948, www.fold3.com], a fact he denied vigorously when questioned by Breitenbach.

Irwin (or Erwin) SiegerAllied investigators were unsure of Sieger’s identity since they had received conflicting reports about the activities of a man bearing that name actively engaged in concealing and dispersing art looted during WWII and stolen from the Führerbau. Under questioning, Dr. Erwin Sieger lived at Olgastrasse 98 in Munich who was known as an “unscrupulous businessman” and a self-described “art amateur”, pledged to assist US authorities with their investigations into the whereabouts of the Schloss paintings and others. [Breitenbach to Leonard, “Information concerning stolen Schloss paintings,” 25 February 1948, www.fold3.com].

|

| Lt. Hugoboom |

The music manIn early 1947, while serving as a MFAA officer in Munich,

Lt. Ray W. [Wayne] Hugoboom received

Portrait of Paulus Pontius as “turned-in loot from the Führerbau” which Hugoboom characterized as a “gift” from the Oberbürgermeister (Lord Mayor) of Munich. However, instead of returning it to the MCCP as he should have, Hugoboom asked Franz Söker in Neu-Gilching if he could restore the damaged painting. It took him about two weeks.

Once ready, Hugoboom hung the painting in his office. He even mentioned to his former secretary, Miss Koslowski, that he had bought it on the black market in Munich and not to tell his superior officer, Captain Rae of the MFAA. Lt. Hugoboom had a black crate made with metal sidings in which to house the painting, ostensibly for shipment. When confronted by Edgar Breitenbach, Lt. Hugoboom contradicted Koslowski’s assertion in a letter dated 3 June 1948. He delivered a contrite apology about his errant ways in the handling of the van Dyck. [Ray W. Hugoboom, School of Music, Indiana Unversity, Bloomington, IN, to Edgar Breitenbach, MFAA, OMGBavaria, 3 June 1948; Breitenbach to Hugoboom, 26 May 1948, www.fold3.com].

The recoveryOn 6 April 1948, Edgar Breitenbach recovered Anthony van Dyck’s

Portrait of Paulus Pontius at the studio of Alfred Koch on Holbeinstrasse 5 (or 43), Munich. According to Breitenbach, the van Dyck painting was the third most important painting from the Schloss collection. As part of his investigation into the circumstances surrounding the van Dyck painting, Breitenbach summoned for questioning Franz Söker to the MCCP on 14 April 1948. [Herbert Leonard, OMGB, to Franz Söker, 14 April 1948, RG 260 M 1946 Reel 137 NARA.

www.fold3.com].

Ray Wayne Hugoboom’s defenseAfter Lt. Hugoboom left Munich in mid-1947 and returned to the United States, he received a promotion to become Assistant Professor of Choral Practice at the School of Music at Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. Hugoboom retold his saga with the van Dyck and declared that “the painting was located in an alley rapped [sic] up in old papers, thoroughly soaked and quite badly damaged.” He largely corroborated his official story—restoration, hanging in his room “for a short time before leaving” and leaving the painting with Alfred Koch “momentarily.” He was so busy with plans for his departure that he forgot to “arrange for [the] return” of the painting to the MCCP. [Wayne Hugoboom to Edgar Breitenbach, 10 May 1948, RG 260 M 1946 Reel 137 NARA].

Breitenbach sets the record straightIn his reply to “dear Hugoboom,” Breitenbach informed him that his letter of 10 May 1948 had caused “considerable embarrassment” at the MFAA. His recounting of the facts did not tally with the MFAA’s investigation.

Firstly, the mayor of Munich did not show him the van Dyck painting and three other paintings. It is Alfred Koch who advised him on the selection. Koch remembered the other paintings very well: two Breughel-like landscapes and a Dutch interior with woman and child. Koch did recall your hesitancy in accepting the gift but that you decided to take it, nevertheless, hoping to donate it “at a later date to some museum.”

Secondly, the story of the gift from the Mayor’s office may have been a hoax. Did Hugoboom partake in it? Unsure. But Alfred Koch and an accomplice by the name of Gillman were certainly in on it. Breitenbach noted that an apology to the Oberbürgermeister was in order. Gillman was also involved as a bit player in the mishandling of another painting from the Schloss collection,

Portrait of a Lady, by Bartholomeus van der Helst.The MFAA ultimately laid the responsibility for the van Dyck affair at Hugoboom’s feet and suggested that the only way to fix it was for him to “make a clean breast” to the MFAA staff. [Edgar Breitenbach to Hugoboom, 26 May 1948, RG 260 M 1946 Reel 137 NARA]. On 3 June 1948, Hugoboom formally apologized to “Mr. Breitenbach.” [Wayne Hugoboom to Mr. Breitenbach, 3 June 1948, RG 260 M 1946 Reel 137 NARA].

Final destination |

| Portrait of Paulus Pontius, Israel Museum, Jerusalem |

The van Dyck painting was repatriated to Paris on 3 June 1948 and restituted to the family of Adolphe Schloss on 6 July 1948. It was sold at Galerie Charpentier on 25 May 1949 (lot no. 17). Madeleine and Joseph R. Nash, an Australian couple living in Paris, acquired the painting. They died on 15 August 1977. Two years later, in keeping with their history of donations to the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the painting was bequeathed anonymously to

the Israel Museum.

Sources

RG 260 M 1947 Reel 137 NARA through www.fold3.com

ERR database

www.errproject.org

The Jewish Digital Cultural Recovery Project (JDCRP) Pilot Project

https://pilot-demo.jdcrp.org/

The Monuments Men and Women Foundation

https://www.monumentsmenandwomenfnd.org/hugoboom-lt-r-wayne

Reviewed and edited by Saida S. Hasanagic

%20Castle.png)