Why Mrs. Zale?

A search of deportation lists for Jews arrested in Nice and surrounding areas in 1943 and 1944 and transferred to Drancy in Paris did not produce any familiar names that might confirm Kellermann’s assertion.

Similarly, there are no postwar claims recorded for either Mrs. Berger or Mrs. Zale. Unable to confirm or infirm Kellermann’s statement to Segy, the search for more information about Mrs. Zale, her son and Mrs. Berger reached an impasse.

Until…

In 2019, Gergely Barki met with Cyla [Csaba Kajdi]—a Hungarian contemporary artist with a huge following on social media—who turned out to be the story’s unwitting gatekeeper.

Cyla’s [Csabad Kadji]’s great-grandfather was Rezso Balint. Barki wanted to know more about the Balint family’s history in interwar France.

Rezso was a Hungarian Jewish artist who had frequented the likes of Amadeo Modigliani in whose studio he had slept several times. Rezso’s brother, Adalbert (or Belá) operated “an important gallery in Paris” using the name Adalbert Berger. In 1912, Balint had met “Juliska Windt (later to be Mamika)[ Juliska (aka Júlia Windt, aka Júlia Bálint (?), aka Julia Berger, aka Julia Kellermann)]/, who was originally from the Nyírség region of Hungary. Juliska was Rezso’s wife until she left him to strike a romantic relationship with Dezso Kellermann, her old flame from Kecskemet whom she had rejected in 1912.

Adalbert [Bela] Berger was also an art collector who amassed works by modernists like Modigliani, Braque, Delaunay, Gondouin, and Czóbel. He died in 1931.

Once the Nazis had taken over more than half of France, they requisitioned Jewish-owned businesses including Julia Berger’s gallery. She fled Paris with Dezso Kellermann, seeking refuge in Nice which, at that time, was occupied by the Italian Army. Julia Berger found an apartment in the Cimiez section of Nice. According to Barki, she managed to elude arrest and deportation by the Nazis. She waited until 1959 to tie the knot with Dezso. His son, Michel Kellermann, has become a fixture in the Parisian art world. establishing himself as a world expert on André Derain, about whose work he compiled a catalogue raisonné.

Work in progress

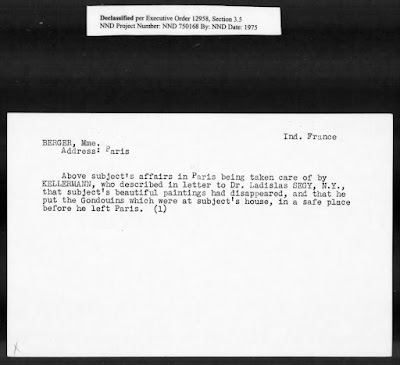

The one—page document detailing an exchange between D. Kellermann and Ladislas Segy on New Year’s Eve 1944 which prompted this short article is easier to understand using the Barki blog piece about the Balints, Bergers, and Kellermanns in France. It has shed some contextual ight on several individuals featured in the intercepted correspondence.

The author of the message, D. Kellermann, is confirmed as Dezsó Kellermann, a Hungarian Jewish art dealer from Kecskemet whose family had settled in Paris before or during WWI. His progeny, Michel Kellermann (not mentioned in the note) is a highly-respected Paris art expert and dealer in his own right.

Mrs. Kale still remains a mystery to us, despite the latter-day revelations from Mr. Barki. Nevertheless, we can surmise that: 1/ Kale is her married name, 2/ she might also be of Hungarian Jewish extraction and 3/ she owned a valuable art collection which was plundered in Nice before her arrest and that of her son.

Mrs. Berger [Juliska Balint/Berger/Kellermann] is of Hungarian Jewish extraction, and connected by marriage and kinship ties to the Balint and Kellermann families. She was active as an art dealer in Paris and perhaps even in Nice. During one of Barki’s interview sessions, Cyla’s mother, Annamaria Basti, a denizen of the French Riviera, had shown him letterhead clearly indicating “Galerie d’Orsel, 16, rue d’Orsel, Paris, Julia Berger.”

For now, we have not found any trace of a postwar claim submitted to the French authorities by either Mrs. Berger, Mrs. Zale or Mr. Kellermann acting on their behalf. Hence, we cannot ascertain the extent of their material losses including art works and objects. An apparent contradiction also needs to be sorted out between Dezsó Kellermann’s assertion that Mrs. Zale, her son and Mrs. Berger were arrested and carted off in “sealed boxcars”, on the one hand, and Mr. Barki’s statement that Mrs. Berger, thanks to her ingenuity and help from a local resident of Nice, was able to avoid arrest and deportation.

Perhaps, the answers lie in Mr. Kellermann’s archives, wherever they may be since he and his family were the closest to Juliska/Julia Berger and Adalbert Balint aka Berger.

Enclosures: Source documents regarding Dezsó Kellermann, Mrs. Zale, Mrs. Berger, and the New Year's Eve 1944-1945 British intercept. These all came from fold3.com, a digital snapshot of various collections stored at the National Archives in College Park, MD.